Growing up, I didn't think of myself as a color. I was just me--quirky, wild, and stubbornly individualistic. I was Jewish. My dad was White. My mom was Native American, African American, and Irish. I was named for my Irish heritage. I was left handed like my dad. I had interesting facts about me, and that's what defined me, not one or two pieces of that story, but the whole thing.

In fourth grade or so, I made a painting that looked something like this:

I made it to convey my ideal of a peaceful world. My dad loved it, told me I should call it "the conception of Erin," which I found wildly embarrassing--both because anything even vaguely about sex was taboo, but also because I hadn't been thinking about myself at all when I created it. I had been thinking about the world outside of my little safe one.

I didn't even realize that most of my friends were white until middle school when there were more black and brown people in attendance. But I was in the honors track--I didn't speak like them or mix with them more than in passing. They weren't my people. And I wasn't their's.

I remember distinctly meeting a new friend in seventh grade who was smart and cynical, like me. I soon learned that she was also interracial like me, which I found delightful. Even though we were mixed differently, it was our sameness I relished. She was just like me! But she was also a dancer, had a Wizard of Oz collection, and liked making cookies. I loved her, and we soon became inseparable.

But middle school was also when I was pushed into understanding that just because I didn't see myself as a color, didn't mean my friends didn't see me that way-- new friends from my new community theater group whose descriptors never started with White to me, but always with the characteristics they defined themselves as: Catholic, musician, actor, gay....

I recall one of these new friends casually calling me Black. I was shocked. I had never been defined by Race to my face before, and I definitely hadn't identified myself as anything to him. It made me deeply uncomfortable. Even though I didn't know why, I was enraged. I shot back that I was Jewish, White, Native American, Irish, too--I had many things in the mix. He insisted that I was trying to deny my Blackness. I shoved him--hard--nearly knocking him into the opening night cake that had been set up in the lobby. Everyone found this hilarious and we all moved on. Even me. Probably, especially me.

Around that time was also when I first read "A Race is a Nice Thing to Have," a book by renowned psychologist Janet E. Helms, who also happens to be my aunt.

At the time, I rejected large swaths of it. It didn't seem right that white people should be thinking of their Whiteness first: wouldn't that make the beautiful melting pot ideal I'd grown up with less than ideal? Wouldn't it be pushing us all to spend more time thinking about race rather than less time? Wouldn't that be bad?

It took me years to understand what a novel and powerful ideal my aunt was striving for. I hadn't realized that my (white) friends were ALL thinking of me as their black friend. Often, I was their only non-white friend--the one they casually brought up with others to validate there own progressiveness.

They didn't think of themselves as a thing. They thought of me as an anti-thing separate from their blank canvas.

And then my eyes opened. My brother and I were traveling from New York to Texas to drop a car off for my parents. In Kentucky, we were driving along a two lane highway when a cop cruiser glided up beside us, looked in, went behind us and pulled us over.

Politely, the cop asked us:

Politely we answered:

Calmly, casually, he asked me to get out of the car. I was extremely aware of the fast moving traffic zooming inches from me. I was aware that my brown brother was being questioned alone in the car, and while he'd been taught what to do, these cops didn't know us and could interpret everything we said however they wanted. I was afraid for him and angry for both of us.

Shortly, I was allowed back in the car and the cops politely let us know they'd pulled us over because we had passed someone too closely awhile back. Drive safe. Sure.

Of course they asked him the same questions as me, trying to catch us in a lie, trying to determine the kind of brown we were.

We didn't talk about it more. We were two brown people driving through the South, and we needed to be more careful. I needed to be more careful with my brother's life.

This incident jolted my brain into reflecting back to other snapshots in my life. Did my mother have to prove herself to the Jewish community so that we, her children, would feel safe there?

Why was it that Sam singled me out after the OJ Simpson trial to tell me he was guilty, even though I was among the few who didn’t express an opinion on the subject?

Did my dad's dad not meet us until we were older because we weren't White?

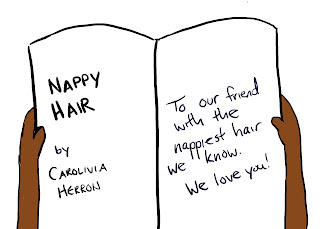

That time when a couple of friends got me a book about nappy hair and inscribed it:

Despite the fact that my hair isn’t nappy at all, it was probably true that it was nappier than anyone else’s they knew.

What about the time one of my closest college friends was meeting me at the airport and thought about how she would describe me to others if we couldn't find each other easily?

Other (White) people got to define me. They got to decide who I was, and if I didn't agree, I was in the wrong, not them.

And this is the world we still live in. A world where White people get to define everyone and make snap decisions about worth and value and threat level. A world where White people are still the measuring stick the rest of us are measured against.

And I understand why my aunt was emphatically opposed to this.

And I understand why people are protesting the deaths of black and brown people.

And I understand why I feel a deep rage and despair.

I just don't know what to do with it.

Amazing post, Erin. It would make a perfect TED talk. I especially loved how you reacted to that boy who was mansplaining to you about your racial identity. A well-placed shove, visually represent the expression, "Get thee away from me, Satan" except instead of Satan, you could substitute the word, fool.

ReplyDeleteHey friend - as always, you are still a thoughtful and incredible writer. Thank you for sharing this. I will do everything I can to do my part and will continue to hope that now is FINALLY the catalyst for change. I miss your quirky, individualistic self! -The Other Erin

ReplyDeleteI love you, Erin. All of you. Miss you. - Anna Gregs

ReplyDeleteErin - long time... growing up, we had a special place, I think. I distinctly remember when I found out you were Jewish. I remember wanting to know more about your family and how it made you, well, you. You were always unique and brilliant. Creative and smart in ways I wasn’t. I never thought of you as my black friend. Or my Jewish friend. Or my thespian friend. You were just your brilliant self who had a different family makeup than mine. Living in Iowa now, I see our childhood differently. I value it a whole lot more, but I find myself trying to explain it to people in terms that aren’t totally correct either. I’m rambling now, but I’m glad someone shared your blog.

ReplyDeleteA dear friend, when we were in high school, after enumerating her heritage, ended by saying, “I’m a mutt.” That got me to thinking; in terms of heritage and ancestry, we all are. No one looking at me would guess I’m First Nation. As appalled as I am by current events, it’s past time to address it, and I am glad.

ReplyDeleteThanks for writing and sharing this blog post. This is very readable and very powerful.

ReplyDelete